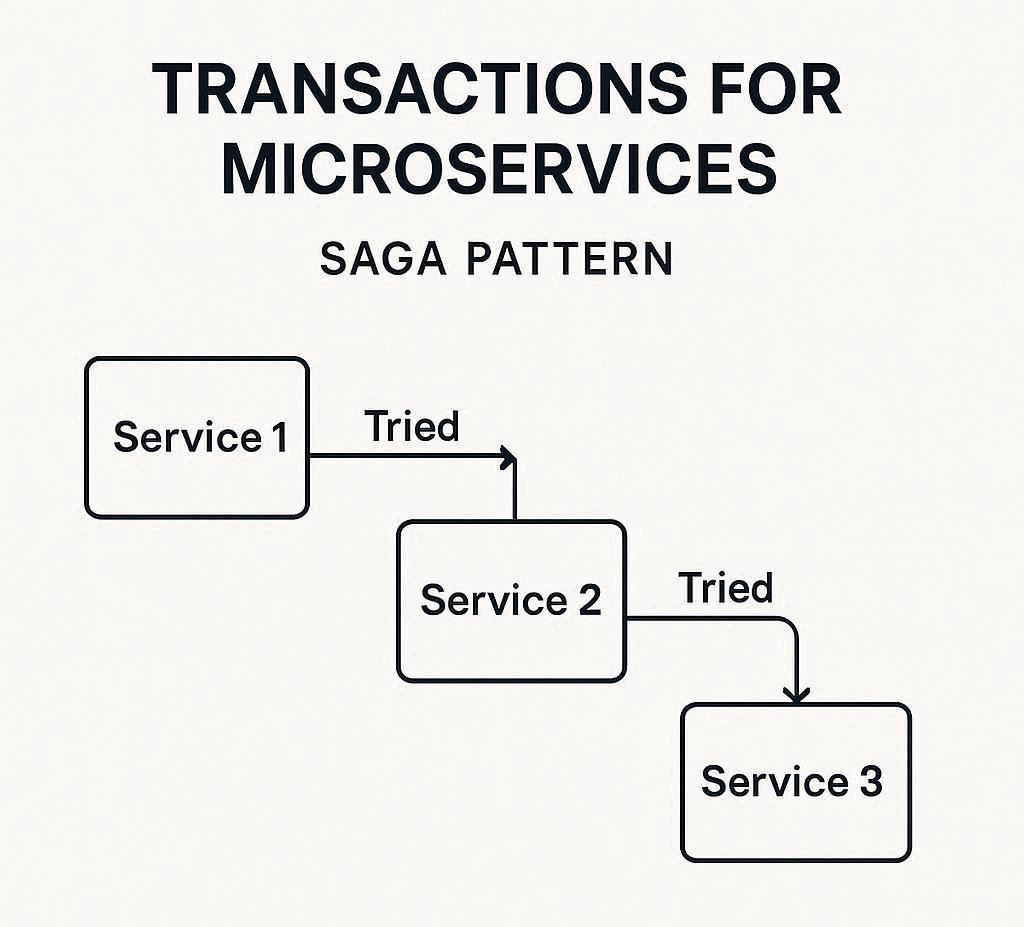

One of the challenges of using microservices is the lack of transactions in operations that span multiple services. We will see how to solve it using a standard pattern.

What are transactions?

Many operations require modifying data in different parts of the system. For example, paying an invoice may require changing its status, modifying an account balance, registering it in a bookkeeping system, etc.

These changes should either happen together or be completely cancelled. Imagine how bad it would be otherwise if, due to an error, the money was taken out of the account, but the invoice remained unpaid, or the payment wasn’t recorded.

Transactions handle this. They track all the places that need to be modified and roll back the changes in case of error. This way, the data cannot get into an inconsistent status. This is usually done at the database level, and we can configure in the application code which changes we want to include in the transaction.

What is the challenge with microservices?

The operations described before may be done in different services (invoice, account, payment, ledger…). Each of them may use a different schema, a database in a different server, or even a completely different type of database.

In these cases, we can use transactions inside a service but not across multiple services. The aim then is to achieve eventual consistency. Some of the data may get into an inconsistent status for a few seconds, and the application code will handle it. There are some ways of doing it, and one of the most common patterns is Saga.

Let’s see an example

We could divide the previous example into a few steps:

- Check that the account has enough balance

- Check that the invoice is active and hasn’t been paid yet

- Deduct the amount from the account

- Change the status of the invoice

- Do the actual payment

- Store the payment in the ledger

- Send notification emails

Note that I have put the validations at the top. This way, we check that we can perform the changes before starting them, so we avoid modifying data and restoring it later if we know from the beginning that the whole operation cannot be done. These validations should be done again later on the operations that modify the data.

Also, please note that I have put the most restrictive operation at the beginning. Different processes may try to pay different invoices with the same account, so let’s modify the account balance first. This way, we will notice any lack of funds as soon as possible.

How can we handle the errors in this example?

There may be different types of errors. For example, the payment API may be down, and we wouldn’t be able to process the payment at that moment, but we could do it after a few minutes, or there may be a bug that doesn’t allow us to write in the ledger, and that would take more time to be fixed. Depending on the case, we may decide to either undo all the previous steps (backward recovery) or try again later the pending ones (forward recovery).

The forward recovery is easy; let’s focus on the backward one: If there was an error in step 3, taking the money from the account (for example, another user may have made another payment in parallel), we could cancel the whole operation. If the error was instead in step 5 (imagine that the banking system is down for a few minutes), we would also have to revert the steps 3 and 4 so the account balance and the invoice have the previous status.

However, we cannot really revert the account balance to the previous amount because other changes may have happened in parallel. For example, the account owner may have topped it up at the same time.

What we could do is to increase the account balance by the amount that we had deducted before. It would work like this:

- The account balance was initially $1000.

- We deducted $100 for paying an invoice, and the balance became $900.

- The account owner topped up $300, and the balance became $1200.

- The payment of the invoice failed, and we topped up $100.

- The balance became $1300.

This way of reverting the changes is called a compensating transaction.

We have to be careful and ensure that the change is idempotent, as a retrier may try to apply the operation more than once (e.g. for timeouts), and it should increase the balance only once. We could do it, for example, by sending an operation ID so the service can check if it has been received before.

How to implement it

The first thing to do is to track the status of the whole operation so we can recover from it in case any part of the system fails. For example, storing it in the database and/or in a log that allows us to see the history of the changes (e.g. Kafka). As mentioned before, in the case of forward recovery, we just have to check later if it is possible to do the operation that failed. This could be done with a scheduler that gets the failed operations from the database or from a queue, and tries them again. Let’s see how to do backward recovery with two types of architectures:

1) In service orchestration architectures: In this case, one service manages the communication between the others, which work separately without knowing about each other. It is usually modelled with a state machine in which we specify the actions that should happen in case everything goes well, and which compensating transactions should be executed otherwise.

2) In service choreography architectures: This is more challenging because the logic to revert the whole operation is distributed between all the services, and they should know which ones they should call in case something goes wrong. Also, adding more services may complicate the whole thing, as we may have to figure out which services we have to change. In this case, we need an operation ID that is sent across the services so they know how to retrieve the information they need to make the changes.

Conclusion

We have seen different approaches to solving the problem depending on the business logic, the error type, and the architecture type. The solutions are more complicated than using a simple transaction in a monolith, but they have advantages as they allow for decoupling the data between services and deploying them separately without losing data integrity. Have you used them? If so, what are your experiences? As usual, I would love to read them in the comments section below.

Leave a Reply